Leg Curl -Deep Dive

LEG CURLS: SEATED, LYING, OR STANDING?

The Best Curl to Build Your Hammies

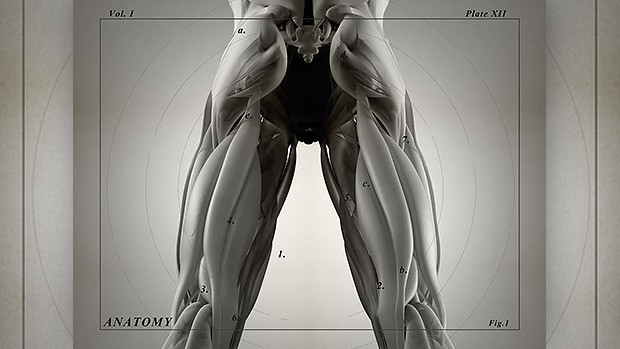

Direct hamstring work is essential whether you’re trying to build size, improve performance, or reduce injury risk. And the leg curl is what most people do to target it.

While most of the hamstrings can be targeted with hip extension moves like the deadlift, total hamstring development requires knee flexion, like from a ham curl. But not all of these exercises are equal.

Let’s think about the musculature here for a second. Because the biceps femoris short head doesn’t cross the hip, the hip position involved with a knee flexion exercise (like a hamstring curl) will not influence its response to training, but it’ll affect three other hamstring muscle bellies.

The semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris long head cross both the hip and knee joints and are biarticular muscles. The monoarticular biceps femoris short head exclusively crosses the knee joint and can only be trained via knee flexion (17).

Consequently, seated, lying, and standing leg curls will similarly develop the biceps femoris short head, but seated leg curls provide distinct benefits for the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris long head.

The Science of Tension

We’re about to geek-out pretty deeply here so put on your anatomy and physiology thinking cap… or just skip to the next section.

Tension is a primary determinant in the magnitude of hypertrophy and strength enhancement induced by resistance training, so proper exercise selection should strive to maximize the tension experienced by the target muscle fibers (15).

This ability of passive tension to contribute to total tension allows greater force to be produced when a muscle is lengthening during an eccentric action than shortening during a concentric action or statically contracting during an isometric action (1,6,7,12,16,18).

Each functional unit of a muscle fiber, known as a sarcomere, contains thin actin filaments and thick myosin filaments. The degree of overlap between actin and myosin determines how much active force can be produced by a sarcomere. And actin-myosin overlap is a function of sarcomere length.

At very short or long sarcomere lengths, actin-myosin overlap is low, therefore little active force can be produced. At intermediate sarcomere lengths, actin-myosin overlap and active force production are greatest. Due to the contributions of passive tension, however, total tension is maximal at rather long sarcomere lengths.

As a sarcomere is elongated beyond an intermediate length, passive tension develops from titin – a spring-like protein named for its immense size – being stretched (5).

When initially transitioning from an intermediate length to a moderately long length, the rate which active force production decreases is greater than the rate at which passive force production increases, resulting in a minor net reduction in total tension.

When further elongating from a moderately long sarcomere length to a very long length, passive force production rises more rapidly than active force production drops, yielding a net increase in total tension that allows for peak tension to be developed at very long sarcomere lengths (13).

Repeatedly exposing muscle fibers to this peak tension while lengthening may induce stretch-mediated hypertrophy, therefore facilitating a greater amount of muscle growth than could be produced by training at shorter lengths (10).

The Best Curl for the Job

Because the biarticular hamstrings are both hip extensors and knee flexors, a position of simultaneous hip flexion and knee extension is required to train them at long muscle lengths where total tension can be maximized.

Think of the position you’re in with seated ham curls. Yep, your hips are flexed and your knees extend and bend.

In a lying or standing leg curl – where the hip is nearly in a neutral position – the biarticular hamstrings operate at moderate to short muscle lengths, where passive tension is minimal.

At the end of their concentric phases when maximal knee flexion is reached, the biarticular hamstrings are shortened at both the hip and knee joints. When shortened at both joints, the capacity of a biarticular muscle to produce active force may become impaired. This phenomenon, termed active insufficiency, results from reduced actin-myosin overlap within the shortened muscle’s sarcomeres (14).

Alternatively, in a seated leg curl, the flexed hip position allows the biarticular hamstrings to operate at moderate to very long muscle lengths where passive tension can be developed and total tension can be maximized.

Research has demonstrated this by finding peak knee flexion torque to be significantly greater in a seated compared to lying position (2,4,8,11,19,20). Over time, exposing your hamstrings to this greater magnitude of tension with the seated leg curl can yield greater gains in size and strength than could otherwise be achieved with the lying or standing leg curl.

This superior hypertrophy was demonstrated by a recent study by Maeo et al. (2020) which compared 12-week leg curl training interventions where each subject had one limb assigned to the seated intervention and the contralateral limb assigned to the lying intervention.

An earlier study by Guex et al. (2016) also found ham curls done with a flexed hip yield greater strength gains than ham curls with a neutral hip.

The seated ham curl group experienced an increase in peak eccentric knee flexion torque that was approximately 39% greater than the supine group (3).

A Place for the Other Curls

Now, this doesn’t mean you should avoid lying and standing leg curls. Both from a psychological and injury risk reduction perspective, exercise variety is beneficial.

Sure, do lying, standing, and seated leg curls. The variety is important for a complete long-term resistance training program, but it would be advantageous to do the seated leg curl MOST often.

The key is to invest the majority of your training time into exercise variants which yield the greatest returns.

Related: One Exercise Isn’t Enough for Hamstrings

Related: The Absolute Best Way to Build Hamstrings

References

- Doss, WS and Karpovich, PV. A comparison of concentric, eccentric, and isometric strength of elbow flexors. Journal of Applied Physiology 20: 351-353, 1965.

- Figoni, SF, Christ, CB, and Massey, BH. Effects of Speed, Hip and Knee Angle, and Gravity on Hamstring-to-Quadriceps Torque Ratios. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 9: 287-291, 1988.

- Guex, K, Degache, F, Morisod, C, Sailly, M, and Millet, GP. Hamstring Architectural and Functional Adaptations Following Long vs. Short Muscle Length Eccentric Training. Front Physiol 7, 2016.

- Guex, K, Gojanovic, B, and Millet, GP. Influence of Hip-Flexion Angle on Hamstrings Isokinetic Activity in Sprinters. J Athl Train 47: 390-395, 2012.

- Herzog, W. The multiple roles of titin in muscle contraction and force production. Biophys Rev 10: 1187-1199, 2018.

- Jones, DA and Rutherford, OM. Human muscle strength training: the effects of three different regimens and the nature of the resultant changes. The Journal of Physiology 391: 1-11, 1987.

- Kellis, E and Baltzopoulos, V. Muscle activation differences between eccentric and concentric isokinetic exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 30: 1616-1623, 1998.

- Lunnen, JD, Yack, J, and LeVeau, BF. Relationship between muscle length, muscle activity, and torque of the hamstring muscles. Phys Ther 61: 190-195, 1981.

- Maeo, S, Meng, H, Yuhang, W, Sakurai, H, Kusagawa, Y, Sugiyama, T, et al. Greater Hamstrings Muscle Hypertrophy but Similar Damage Protection after Training at Long versus Short Muscle Lengths. Med Sci Sports Exerc , 2020.

- McMahon, G, Morse, CI, Burden, A, Winwood, K, and Onambélé, GL. Muscular adaptations and insulin-like growth factor-1 responses to resistance training are stretch-mediated. Muscle Nerve 49: 108-119, 2014.

- Mohamed, O, Perry, J, and Hislop, H. Relationship between wire EMG activity, muscle length, and torque of the hamstrings. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 17: 569-579, 2002.

- Nogueira, FRD, Libardi, CA, Vechin, FC, Lixandrão, ME, de Barros Berton, RP, de Souza, TMF, et al. Comparison of maximal muscle strength of elbow flexors and knee extensors between younger and older men with the same level of daily activity. Clin Interv Aging 8: 401-407, 2013.

- Odegard, G, Donahue, TL, Morrow, D, and Kaufman, KR. Constitutive Modeling of Skeletal Muscle Tissue With an Explicit Strain-Energy Function. Journal of biomechanical engineering 130: 061017, 2009.

- Schoenfeld, B. Accentuating Muscular Development Through Active Insufficiency and Passive Tension. Strength & Conditioning Journal 24: 20-22, 2002.

- Schoenfeld, BJ. The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 24: 2857-2872, 2010.

- Seliger, V, Dolejš, L, and Karas, V. A dynamometric comparison of maximum eccentric, concentric, and isometric contractions using EMG and energy expenditure measurements. Europ J Appl Physiol 45: 235-244, 1980.

- Stępień, K, Śmigielski, R, Mouton, C, Ciszek, B, Engelhardt, M, and Seil, R. Anatomy of proximal attachment, course, and innervation of hamstring muscles: a pictorial essay. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27: 673-684, 2019.

- Tourny-Chollet, C, Leroy, D, Léger, H, and Beuret-Blanquart, F. Isokinetic knee muscle strength of soccer players according to their position. Isokinetics and Exercise Science 8: 187-193, 2000.

- Worrell, TW, Perrin, DH, and Denegar, CR. The influence of hip position on quadriceps and hamstring peak torque and reciprocal muscle group ratio values. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 11: 104-107, 1989.

- Yanagisawa, O and Fukutani, A. Muscle Recruitment Pattern of the Hamstring Muscles in Hip Extension and Knee Flexion Exercises. J Hum Kinet 72: 51-59, 2020.